I have been given a little shove to take part in a blog chain about writing processes. Thanks go to shover Kim Kelly, writer of colourful and gripping historical romance and keeper of a fascinating and inspiring blog about sources and much more at KK Author Lady.

I have been given a little shove to take part in a blog chain about writing processes. Thanks go to shover Kim Kelly, writer of colourful and gripping historical romance and keeper of a fascinating and inspiring blog about sources and much more at KK Author Lady.

If you have read my blog previously, or know me personally, you will be aware that it takes me a while to get around to things. I like to think that this is because my plans are large and my person small, so some time must pass while I grow to meet my ambitions. This often takes a while, so some of what follows will be on a popular theme of mine: getting around to it.

So . . . what am I working on now?

I am working (mostly in my head while driving) on a contemporary novel about a family in which a grim secret is being kept from one of the siblings. Because poor old Jemima is being kept in the dark, she is going to keep poking around until she causes terrible trouble for all concerned. I hope that the book is going to be grim, funny and compelling, because without hope, what are we? (Sad, and sleepy, speaking for myself.)

How does my work differ from others in its genre?

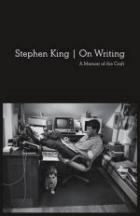

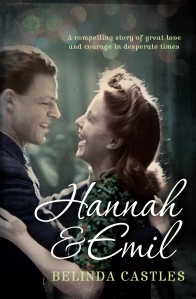

I don’t think that I work in genre, although I’d like to borrow a bit of crime for this one, if no one minds. My books so far have been quite different from one another (Falling Woman – coming of age in the city/ The River Baptists – secrets playing out on a river island/ Hannah and Emil – historical fiction) but I suppose what they have in common is a fascination with people and what they mean to one another. We are all so vulnerable to love and rejection and loss. Poor us! But it does make us interesting. I also love books that are set against evocative backdrops, so I think that setting is always a feature too.

Why do I write about what I do?

My last book was different to my previous novels in that it was about the actual lives of my grandparents, who had such interesting lives that I had always wanted to find out more about them and to tell their story. But for my more ‘made up’ novels, it is usually a combination of a place and a person that starts niggling, and probably changes a lot, often being rejected in favour of someone and somewhere more interesting. It is just a way of thinking, figuring out what people might do in given situations, what pressure will bring out of them. You have to follow it through.

How does my writing process work?

Well, I dictate the first draft to my handsome assistant over a period of ten weeks, during which no one is allowed to call or visit in case they interrupt the flow of inspiration; then he types it on a 1960s Olivetti onto cream 180 gsm paper from Florence, ready for my marginal notes. I often come upon him laughing, or weeping over the typewriter, and have to hurry him up a little…

Ha ha. I don’t know. I write in the car, in the library, in bed, in cafes, thousands of words a day or a couple of lines, sometimes not for months, sometimes all the time, taking walks, making big decisions while I walk, coming home, writing some more. It is not romantic to say it, but looking after my children and earning a living are usually a much higher priority, because they have to be. But I am always looking for an opening. My husband is taking the kids somewhere, paid work has gone a bit quiet…Aha! Time to write. It’s like trying to keep your mind still in meditation. You’ll never sustain it, but if you keep coming back to it, you’ll get what you need to done.

Here is where I introduce you to two more writers who as far as I can tell get a lot more done than I do and with grace and humour to boot.

Angela Meyer

If you’ve been to a literary festival in Australia you will know Angela as an imperturbable panel chair. She is also a prominent literary blogger at Literary Minded and as of this week is to be known as Dr Literary Minded, as she has just graduated from the Writing and Society Research Centre at UWS. She also has two books out this year: The Great Unknown (as editor) and a book of flash fiction, Captives. When Angela comes down off the graduation high, you will be able to find her thoughts on process here: Angela’s blog. I know Angela from our days at Writing and Society, which is a gorgeous oasis of ideas, experience, literary productivity and conviviality in an occasionally slightly dull world.

Lee Kofman

Lee is a writer with an interesting and unusual background. A Russian-born Israeli, her writing career began with three novels written in Hebrew, but since 2002 she has been writing exclusively in English and publishing short stories, creative nonfiction and poetry widely in Australia, Scotland, UK, USA and Canada. Lee’s recently completed memoir The Dangerous Bride about non-monogamy in love and geography will be out in October 2014 with MUP. You can find out her thoughts about the writing process here: Lee’s blog. Lee also blogs monthly on the Writers Victoria website. I met Lee several years ago at Varuna in the Blue Mountains, another epicentre of writing activity and a place close to my heart for its calm writerly buzz, stream of lovely souls like Lee and inspirational cooking from the famous Sheila.